Flow My Tears

Flow My Tears comes from a Philip K Dick novel, which in turn echoes the title of a piece of music composed in the 16th century by John Dowland. While very different media, both Dick’s novel and Dowland’s composition delve the depths of loss specific to this mortal coil and reveal a new psychological landscape—a reality transcending what is typically thought humanly possible.

The lyrics to Dowland’s piece (penned by Dowland himself) unveil a newfound sympathy for all that is shadowy, for a new form of conscience which validates itself apart from considerations of worldliness:

“Harke you shadowes that in darcknesse dwell,

Learne to contemne light,

Happie, happie they that in hell

Feele not the worlds despite.”

Dick for his part, shows how the rage that follows in the wake of shattered illusions can invest a person with a higher kind of power, an inner strength so indomitable as to feel iron-clad and machine-like. In this passage from Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, a woman’s jealous rage lends her an almost humanoid strength:

“When he entered Marilyn’s apartment he saw, at once, that she was out of her mind. Her entire face had pinched and constricted; her body so retracted that it looked as if she were trying to ingest herself. And her eyes…. Her eyes, completely round, with huge pupils, bored at him as she stood silently facing him, her arms folded, everything about her unyielding and iron rigid.”

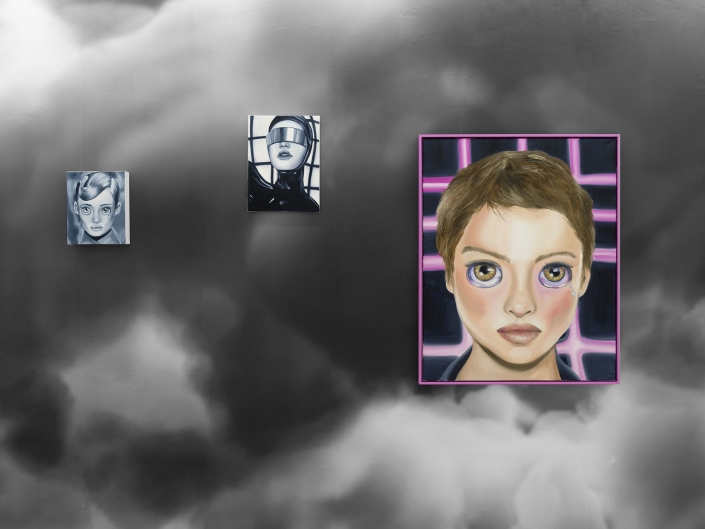

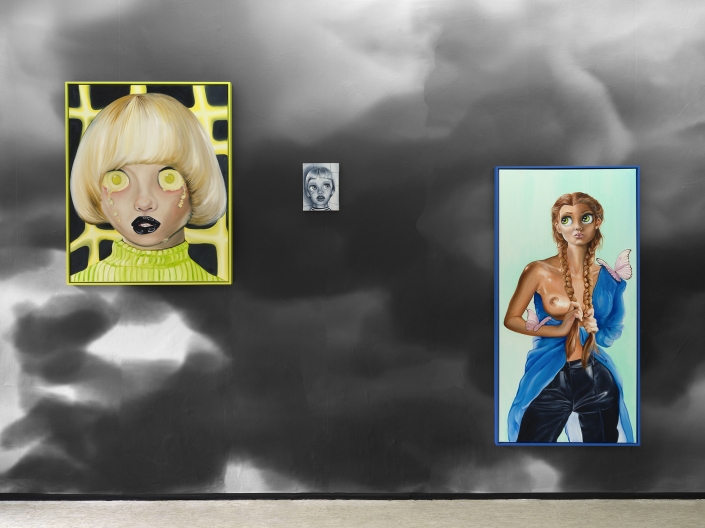

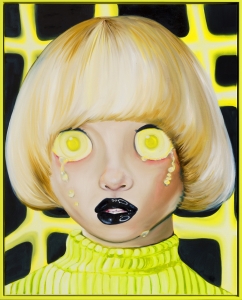

Both Dowland and Dick show us how intensity of feeling can beget a qualitatively new emotion, capacity, vista. Charlie Stein’s paintings of robots depict something similar, but in the reverse.

There’s an enervated aura of charity, the delineations of a dutiful act of generosity, embedded in the expressions of Stein’s robots. These humanoids are supposed to be separate from us, better in every possible respect; yet they set about to emulate what they can never understand. Without motivation, will, or feeling, they’re mimicking that which transcends their programming entirely: the transformative experience of undergoing sorrow.

Throughout Flow My Tears, an unstated tragedy lies in the fact that Stein’s robot women are unable to authentically express sadness, and yet they mirror the gesture of crying—as convincingly as any smoke and mirror show designed to emulate the real thing, from VR to Tim Leary-styled LSD evangelism. The problem here is that, however much Stein’s robots affect the outward trappings of sadness or grief, they can’t actually integrate a sense of poignant absence into the plenum of their programming.

Robots, by design, are objects and thereby self-identical with themselves: they are the concept that they represent, the mechanism that has engendered them. Humans, by contrast, are forever at odds with themselves. We’re always de trop, sempiternally out of step with our inner desires. Yet it’s this very experience of lack which shapes our ideals of transcendence.

In Stein’s robots, the experience of tragedy shimmers with a definitionally finite meaning. In their burnished bodies, we see what’s best in us, and, by that very stroke, what we might revile most about ourselves: our failures, hopes, unrequited needs. Even our mortality stares back at us through the windows of their eyes, like a crater left where an asteroid tears into earth’s mantle.

But Stein’s enhanced humanoids are nothing to envy. In their augmented features, in their perfected femininity, in the way they project their faux sincerity onto the perspective of the viewer, they’re an alienated image of ourselves. They represent everything we cannot assimilate, everything we can never become: the unattainable ideal of being a singular identity that exists harmoniously at one with itself. Despite their flow of tears, they’ll never understand the indefinite expanse of a world which is only felt, and remain forever blind to the shadows that in darkness dwell.

Text: Jeffrey Grunthaner

Charlie Stein: Flow My Tears, Bark Berlin Gallery, 2022